With specific commentary on El Pecado (1913) & La Gracia (1915)

In the Plaza del Porto, the more intrepid visitor can discover that there is more to Córdoba than the Mosque-Cathedral and its surrounding reminders of the city’s former status as one of the world’s great cultural centers when it was the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate. There, somewhat obscurely located, one will find the birthplace and museum of the city’s patron artist – a man of scant renown and limited fanfare beyond the borders of Spain – Julio Romero de Torres (1874-1930): painter of the Cordovan soul and the man that Valle-Inclán deemed the “first Spanish painter”.

Born in Córdoba in 1874 to a father who was curator of the city’s Museo de Bellas Artes, Julio Romero de Torres is an artist whose work seems almost stereotypically Spanish on its surface. Bullfighting, flamenco performers, gypsies and Catholicism: all of these are prevalent across his nearly 1000 paintings, leading to labels of “kitsch” from a number of critics. Yet, perhaps the greatest eye-roll inducing aspect of his work can be found in his greatest source of inspiration: the female form. Overwhelming a painter of women, often in provocative and lascivious poses, this emphasis has further bolstered such assessments, while also subjecting him to feminist critiques. Here again, Romero’s work can come across as an antiquated cliché of Spanish culture that reinforces gender disparities and objectification of women through a brush informed by the masculine culture of machismo and its claims towards how women should be viewed and the roles they should assume.

Naranjas y limones (1927)

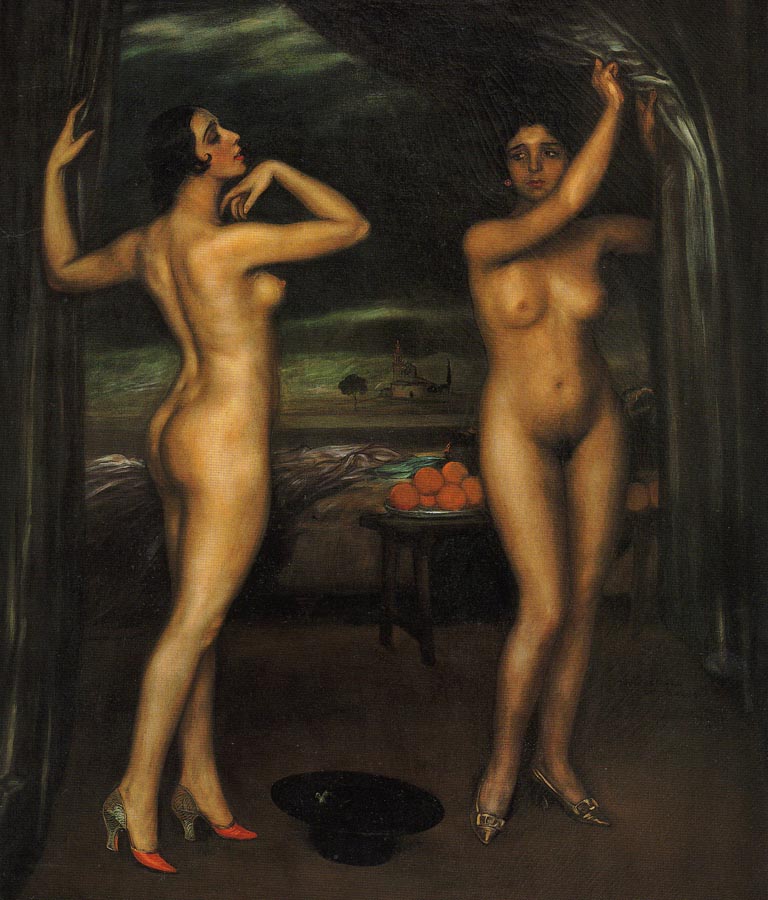

Rivalidad (1925-6)

Cante Jondo (1929)

La musa gitana (1907)

La Nieta de Trini (1929)

While not dismissing these views entirely, I would like to challenge them through an analysis of two works found in the Julio Romero de Torres Museum. In so doing, I expect to show that there is greater depth to Romero’s art than typically perceived. I hope, moreover, to highlight that – as reflected in the adulation he received from his fellow Cordovans for his depiction of these quintessentially Andalusian cultural forms – Romero’s art provides the modern viewer with a valuable resource for understanding the culture of this region as it existed in the late 19th and early 20th century. By using his brush to capture his compatriots’ culture as they experienced it, we shall see that Romero provides a lens through which the outsider can obtain greater insight into a culture that is often difficult to access.

El Pecado and La Gracia

Among the number of interesting pieces housed in Córdoba’s Museo de Julio Romero de Torres, there are two that I find particularly compelling and which serve as the main focus of this article: El Pecado (1913) and La Gracia (1915). Produced two years apart, these paintings are noteworthy in that they can be viewed either in isolation or together as part of a sequential narrative. This is especially interesting because it highlights the importance of context in shaping our interpretations of a work of art and demonstrates the nuances involved in the production of meaning between artist and viewer.

As it appears that Romero intended for the two paintings to be viewed as part of narrative, I would like to honor these intentions and review these paintings sequentially, beginning with El Pecado and then moving onto La Gracia.

Translated into English as “the sin”, El Pecado presents a young, nude woman, laying sideways on a bed with her back to the viewer. Facing her, we observe three elderly women dressed in dark, solemn attire: one holding a hand mirror directed at the protagonist, who is listening to the other two as they engage in what appears to be an impassioned discussion. A fourth woman of similar age can be seen at the feet of the young woman, smiling as she extends what appears to be a golden apple. Reflected in the mirror we catch the young woman’s gaze: a distinctly Andalusian countenance portrayed in a manner frequently observed in the artist’s work – dark, provocative and inviting, but distant and with an air of melancholy. Her eyes are not the only ones directed towards us, however, as we similarly find the holder of the mirror staring at us. The young woman lays upon opulent bedding, adorned with silk/satin sheets of white, purple and gold (possibly her clothing). At her feet, we see a rose and note her golden shoes conspicuously placed beneath the footing of the bed. In the background, we can spot Córdoba’s Church of San Hipólito as well as the Castillo de Almodóvar further in the distance.

Moving next to La Gracia (“the grace”), we find a painting quite similar in its compositional structure. As in El Pecado, we are presented with a young, attractive and naked protagonist accompanied by four women set against scenes from Córdoba[i] (painted on a canvas of identical dimensions). Despite this compositional similarity, however, we immediately observe a clear contradiction in the painting’s depiction – an outcome only apparent in the context of a comparative dialogue between the two paintings. Whereas El Pecado centers on the profane, La Gracia counters by focusing on the sacred through a scene that clearly invokes imagery of the Lamentation of Christ following the Descent from the Cross.

Raphael (1507)

A. Dürer (c. 1500)

A. Bergognone (c. 1485)

A. Benson (16th c.)

G. David (1515-23)

S. Botticelli (1490-2)

Romero de Torres (1915)

Using the “Lamentation” as a reference point, the female protagonist in La Gracia is notably occupying the place of Jesus, with her pose and attire strikingly similar to that given to the latter in most artistic renditions of the Lamentation. Although this scene is often cast with a range of characters, it typically includes the Virgin Mary (often holding Jesus’ lifeless body and grieving over the loss of her only son), Mary Magdalene (often positioned at the feet of Christ), John the Apostle and Joseph of Arimathea. In this case, the older woman sitting in the chair would ostensibly play the role of the Virgin Mary, while the nuns at the protagonist’s feet and back could, respectively, represent Mary Magdalene and either Joseph or John. The fourth woman – sobbing and dressed in black – has a less obvious parallel, but would appear to be in line with other anonymous figures in Lamentation paintings who are shown grieving over the body of Jesus.

Based on what we’ve noted thus far, the paintings offer what appears to be a fairly straightforward interpretation in their depiction of the conflict inherent between secular (Pecado) and religious (Gracia) concerns. According to this (standard) interpretation, the act of sin is one found in the pursuit of earthly pleasures (notably material wealth and sex), with the protagonist’s acts from Pecado resulting in a loss of purity and requiring crucifixion and divine forgiveness in Gracia.

This interpretation seems logical, particularly given that this would appear to align with earlier works by Romero – such as Amor sagrado, amor profano (“Sacred love, profane love”, 1908)[ii] and Las Dos Sendas (“The Two Paths”, 1912) – which appear concerned with the duality between sacred and profane. Las Dos Sendas, in particular, appears to lend support to the view that these paintings are merely a reproduction of these previously explored themes.

Amor Sagrado, Amor Profano (1908), Oil on canvas

Las Dos Sendas (1912)

Oil and tempera on canvas

Completed in the year prior to El Pecado, Las Dos Sendas provides easily understood symbolism and seems to be an obvious precursor to the themes developed in Pecado and Gracia. Again, Romero portrays a young, nude female protagonist, laying sideways on a bed adorned with luxurious silks/satin. In the background, two paths are presented, displaying the opposing lives that the protagonist can choose to follow. On the right, we find a portal into a profane existence, highlighted by earthly endeavors and transient pleasures. On the left, the protagonist is instead provided with a religious path devoted to spiritual pursuits. In this context, the narrative presented across Pecado and Gracia seems to be either a retelling of this story or the subsequent chapters of a trilogy that follows the journey of a hero who is presented with a choice between profane and sacred in Las Dos Sendas; opts for the former in El Pecado; and who is crucified for this choice (and potentially redeemed) in La Gracia.

Seen through this lens, many common criticisms of Romero would seem to gain support. The symbols in this case would appear to be so transparently obvious as to make the viewer roll her eyes, providing ammunition to voices that label him as kitsch. Similarly, this interpretation would seem to lend credence to feminist concerns that view Romero de Torres’ work as chauvinistic. The sin, in this interpretation, would appear to center on a woman’s sexuality, with the golden apple invoking references to Eve and the forbidden fruit. That the protagonist would appear to be receiving punishment for this act in La Gracia, appears to cast Romero as a misogynist who uses his art to objectify the female form while similarly shaming women in an attempt to reproduce a patriarchal social structure – often stereotypical of Catholicism and Spanish machismo – that exerts rigid control on women and their bodies.

While it is possible that this interpretation is accurate, I would like to challenge this perspective and offer an alternative as it pertains to these two works of art.[iii] To do this, I would like to return to the first piece and delve deeper into the question of the “sin” being portrayed by Romero. This is going to require a deep dive into Greco-Roman mythology and drama, which I would (apologetically) argue is essential to forming a fuller understanding of this painting (as well as a clever juxtaposition itself, in that it draws from a system of beliefs heretical to the Christian iconography found in La Gracia).

First, let’s refocus our attention away from the action in El Pecado and instead direct it towards the background and Romero’s usage of Cordoba’s Church of San Hipólito. While easy to dismiss given its minor role, I would argue that this specific church’s inclusion is not only deliberate but crucial to our interpretation. Instead of referring to St. Hippolytus of Rome, we might consider that Romero is invoking the protagonist of the Euripides tragedy, Hippolytus. Initially performed in 428 BCE, this classic of Athenian drama presents the story of Hippolytus, offspring of an illegitimate affair between Theseus, King of Athens, and the Amazonian queen, Hippolyta. [iv]

In this tale, Hippolytus is presented as a man of strict adherence to his principles and has taken a vow of chastity as a means of honoring his patron goddess, Artemis. Unfortunately, Greek gods tend to behave like modern day teenagers and Aphrodite, goddess of love, beauty, desire, passion and sexuality is displeased by this, viewing chastity as a personal affront. Being a mature, emotionally secure goddess, Aphrodite then takes the measured step of swearing to enact vengeance against Hippolytus and concocts a scheme where she will get his stepmother, Phaedra, wife of Theseus and queen of Athens, to fall in love with him so that Theseus will carry out revenge against Hippolytus on her behalf.

Ultimately, this is exactly what happens. As a brief summary:

- Phaedra falls madly in love with Hippolytus while her husband, Theseus, is serving an extended absence away from Athens;

- her loyal nurse tells Hippolytus that his stepmother totally thinks he’s cute and that he should go for it;

- Hippolytus vehemently rejects the proposal, but has sworn a vow of secrecy to the nurse so that he is unable to tell his stepfather (when he finally returns);

- Phaedra decides to kill herself but first pens a suicide note saying that Hippolytus raped her so that she may retain her honor and so that her children may retain their claim to the throne;

- Theseus returns, finding that his wife has hanged herself as well as the note;

- Furious, Theseus banishes Hippolytus from the kingdom of Athens;

- Hippolytus is confronted but honors his previous vow of secrecy and does not inform the king of his wife’s advancements, instead standing by his principles and leaving Athens that day aboard his chariot;

- Poseidon, god of the sea, owes Theseus three curses that he can use against any of his enemies, so the enraged Theseus choses to use one against Hippolytus;

- while riding away from Athens, a giant bull (summoned by Poseidon) emerges from the sea and startles Hippolytus’ horses, throwing him from his chariot;

- Hippolytus gets caught in the reins and dragged for some distance, hitting his head against rocks which eventually leads to his death;[v]

- Hippolytus’ nearly lifeless body is brought to the palace where Artemis appears and tells Theseus the truth about his wife and Hippolytus;

- Hippolytus dies and Theseus is overcome with grief at the error of his ways that led to the death of his son. (For anyone interested, a slightly more detailed summary can be found in the annex).

As it so happens, Euripides’ play was later revisited during the Roman era by philosopher, dramatist and noted son of Córdoba, Seneca (the Younger). Alternatively titled as Phaedra, the Seneca version presents a plot that is largely consistent with the original, but which differs in several aspects. Perhaps most notable among these is that it places far more importance on the family lineage of Phaedra and Theseus, while limiting the direct involvement of the gods. Through this latter alteration, greater agency is ascribed to Phaedra, allowing her to be cast more easily as the female temptress trope and employ her feminine seductiveness to corrupt a morally upright younger man. The Seneca version, then, generally consists of a married woman seeking to seduce a younger man; his rejection of her; the woman’s accusation of rape out of anger from being scorned; her husband’s blind faith in the accusation; and, finally, the demise of an innocent young man at his father’s hands.

These two versions of the story of Phaedra, Hippolytus and Theseus together broaden our potential understanding of the two paintings and offer a range of additional interpretations. To begin, we might consider a situation where Romero may be casting himself in the role of Phaedra (a gender reversal true to his use of a woman in the place of Jesus in the Lamentation), with the painting in turn depicting the sin of a married man (Romero/Phaedra) lusting after a younger woman (The young model/Hippolytus). Through this lens, the paintings convey the artist’s struggle between his sexual desire for his muse and his yearning to honor the vows of his marriage and abide by the duties imposed upon him through religion and society.[vi]

In line with this interpretation, there seems to be a strong counterargument within Pecado, which would have us entertain the idea that the sin could be seen as not succumbing to this desire and not indulging our natural, sexual needs. In this respect, we again find support from the Euripides version of the play which ascribes blame to Hippolytus in the tragic outcomes that arise by presenting his ascetic and moral rigidity as culpable in the events that unfold. However, most supportive of this interpretation would, in my opinion, be the painting’s contrasting use of elderly women vis-à-vis the young protagonist.

Rather than the mirror, we might envisage a scenario where it is the elderly women who cast a reflection of the young protagonist by signaling what awaits her with the passage of time. From this perspective, the sin could be conceived of as the protagonist – so striking and in the prime of her life – letting her beauty go to waste. Is it not a sin to let a ripe fruit go uneaten before it rots? Juxtaposed to the elderly women, we are reminded of what awaits the protagonist’s physical beauty, but we also recall the role that our elders play in enforcing social controls against female sexual promiscuity (and which lead to the punishment observed in La Gracia). The woman holding the mirror, in this sense, can be seen as a reflection of the protagonist in the future: the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. If this is what awaits her, the sin then may be viewed as failing to make use of this God-given beauty; of letting something go to waste and not appreciating it while one is in possession of it. To eat or not eat the apple? Which is the greater sin? I would suggest that there is a serious case to be made that Romero is at least entertaining this debate. Indeed, the great challenge often facing us when confronting a choice between “right” and “wrong” is not in deciding which to choose, but rather convincing ourselves of which is actually “right”. Were this not the case, there would be very little dilemma between sacred and profane and it appears, for this reason, that Romero too may be attempting to capture this within the two paintings.

The moral dilemma regarding the sin of wasted youth is one that we find Seneca giving notable attention to in Phaedra. The Chorus that concludes Act II, for example, laments the quick passage of youth and its associated physical beauty while advocating that we “enjoy it and revel in it while [we] may”:

Beauty, you double-edged boon for mortals, brief is your gift and of short duration. How swiftly you flee on those scurrying feet! No quicker are meadows that bloom in the springtime despoiled by the blistering heat of the summer, when long August days start to swelter at noontime and unequal nights race along shorter courses. No quicker do lilies grow pale and start wilting or roses that grace human temples start fading, than radiant blush on fair cheeks starts abating, the victim of time. Every day, every moment comes ravaging bodily splendor and beauty. A fleeting possession is beauty. Be prudent, rely not at all in this blessing so brittle: enjoy it and revel in it while you may! Time silently wears you away, and the moment that passes you by is pursued by a worse one.

In further quoting from Phaedra’s nurse as she confronts Hippolytus in Act II and attempts to persuade him to abandon his vow of celibacy, we may imagine the following expression of sentiments being similarly held by Romero with respect to his lust for the young female protagonist.

Come, remember that you’re young! […] Enjoy your youth – it will quickly pass you by…Let your spirit soar! Why do you lie in a bed of loneliness, without a mate? Unfetter your youth from this gloom. Hurry up, get in the race now, give yourself free rein. Do not let the best days of your life slip away! God has mapped out for us different tasks as he leads us through life in stages: happiness befits the young, a sour face the old. Why hold yourself back? Why stifle your true nature? The field that gives the farmer great profit is the one that, when sprouting, is allowed to abound in lush shoots, and the lofty tree that towards over the grove is the one never pruned or cut back by a stingy hand. Noble men more easily reach their full potential and status if their minds are nourished by a vigorous freedom […] Come, let us imagine a world without Venus, who restores and replenishes deleted species. What’s left? Decay, squalor, rot.

Certainly, we can imagine the artist struggling, like Phaedra, to adjudicate between his desire to join his muse in her “bed of loneliness” while acknowledging that the act could bring shame to his family and dishonor to the vows he has sworn before God. As Phaedra states (from line 380) in Euripides’ Hippolytus:

We know the good, we see it clear.

But we can’t bring it to achievement. Some

are betrayed by their own laziness, and others

value some other pleasure above virtue.

There are so many pleasures in this life –

long gossiping talks and leisure, that sweet curse.

Then there is shame that thwarts us.

In addition to the story of Hippolytus, classical references can be found in Romero’s inclusion of the golden apple. While many interpretations place greater emphasis on the parallel of the apple to that of the forbidden fruit from the Garden Eden, it is my contention that it is more properly viewed as an allusion to the Golden Apple of Discord which played a pivotal role in the Ancient Greek tale of the Judgement of Paris. This apple, which was to be given to the most beautiful, was claimed by Hera, Athena and Aphrodite with the impartial Paris ultimately awarding it to the latter (see endnote for further details).[vii]

In this context, we may instead view El Pecado’s granting of the golden apple to the female protagonist as a signal that she is a representation of Aphrodite. This interpretation is further supported by the similarities between the female protagonist and Diego Velázquez’s depiction of the goddess in the Rokeby Venus (ca. 1647-1651). With this in mind, the protagonist takes on an added abstraction by serving as a portrayal of the goddess of love, beauty, fertility, desire and sex, thereby making her an allegorical representation of the idealized form of these traits. The reference to both the Judgement of Paris as well as Hippolytus/Phaedra again highlights the double-edged nature of passion, desire and attraction based on sexual and physical characteristics. In the latter, tragedy occurs because Aphrodite is not properly honored (and thereby sex, beauty, love, etc.). However, in the Judgement of Paris, honoring Aphrodite nevertheless produces a tragic outcome as it ultimately ignites the Trojan War. Therefore, while the golden apple clearly serves to remind us of the danger that accompanies beauty, we are again reminded that one’s desire of it is more nuanced and cannot be neatly placed within a simple dichotomy of right and wrong.

Rokeby Venus (1647-53)

El Pecado (1913)

While I am less confident of this next assertion, I find it interesting to consider the additional role that the Judgement of Paris might play in helping us further understand the scene portrayed in Pecado. Though perhaps a bit of a reach, it is possible that the two elderly women arguing aside the woman holding the mirror may represent the goddesses Hera and Athena, who, as mentioned, were Aphrodite’s competitors for the golden apple. Seeing already in La Gracia that Romero is comfortable casting women in male roles, it is therefore possible that the woman holding the mirror could be seen as Paris with the mirror signaling his choice of beauty and the promise of love over glory and wisdom. To this extent, we find several artistic representations from periods predating Romero that depict Athena and Hera in a contentious fashion in response to their disagreement with Paris’ decision.[viii]

The Judgment of Paris

Frans Floris (1550)

The Judgment of Paris

A. van der Werff (1716)

As a final consideration, let’s examine the potential implications that may be implied in Romero’s decision to have our eyes being met by both the female protagonist and the older woman holding the mirror. Their looks are penetrating, as though they see us men for what we are: lecherous, desiring to take away the protagonist’s purity. Instinctively, our eyes are drawn initially to the young, naked woman and we male viewers find ourselves, reflexively, objectifying her. When we shift our eyes upwards, we notice the older woman observing us – her scowling look of disapproval leaving us almost ashamed for having been caught in the act, forgetful of social decorum and devolved towards our baser and more lascivious natures.

This interpretation turns the feminist critique on its head, for it suggests that Romero is ascribing the sin to men. It is men who lust after these younger women and attempt to entice them into abandoning their purity – just as Phaedra had attempted to do with Hippolytus. It is, similarly, men who then perpetuate a social system that punishes these same women – labelling them with any of the seemingly endless array of negative terms we’ve devised for shaming female promiscuity – and which chastises them for giving us what we want; while escaping any such labels ourselves.[ix] We who have tempted them into sin, turn around and label them a foul temptress who has led us towards a path of sin. In that mirror, then, it can be asserted that the protagonist sees a reflection of the evilness of men. As Phaedra notes in Hippolytus (from line 427):

Time holds a mirror, as for a young girl,

and sometimes as occasion falls, it shows us

the evildoers of the world…

This brings us then to La Gracia. Whereas the standard account views it as a representation of atonement for the sins of the female protagonist in Pecado, the preceding discussion has provided us with an alternative framework of interpretation. Focusing on the painting’s already observed similarity to the Lamentation of Christ, it should be noted that Christ did not die for actions that would seem worthy of punishment. This is important because it provides further context for how we might understand the characters surrounding the protagonist in La Gracia. Specifically, if we agree that the elderly woman seated in the chair is playing the role of the Virgin Mary, we find our understanding of what is transpiring in the scene altered by specifically challenging the standard account that views her as forgiving the female protagonist (ostensibly for the sins of materialism, lust and vanity this account generally ascribes to Pecado).

It is patently obvious to even someone as ignorant of the New Testament as myself that Mary does not forgive Jesus, but rather those responsible for the death of her son. She forgives us. This then supports the shift of the sin in Pecado away from the female protagonist and onto the viewer – with particular reference again to men and the patriarchal society they reinforce (as already described). If this woman is being persecuted in Gracia for committing a carnal act, it is not because she is guilty; it is because we are. We men are guilty for imposing these rigid constraints on women. The sin is, then, that of social control and the double standards placed on women that forbids them from enjoying the fruit of their youth.

The female Christ-figure has not lost her purity; she has had it taken from her (as symbolized by the weeping young woman who is holding a white lily – a symbol of purity). Just as it is true of the lifeless Christ after descending from the cross, we realize that the genuine sinners have not been punished and that Jesus is a victim rather than a criminal. We require punishment for the crimes we have wrought, but we are similarly forgiven: for the sin of creating a cruel and impossible world where we cajole women into giving themselves to us and then crucifying them when they do

Grace, indeed, is very much an element that speaks to both portraits as can be observed when we delve deeper into its meaning within Christianity. In Catholicism, we are broadly provided with two categories of grace (both of which are seen as gifts from God): sanctifying grace and actual grace. Whereas the former is identified as God’s granting of eternal salvation and rebirth, actual grace may be seen as the light from God that illuminates the proper path and grants us the strength to follow it. The grace of God abounds in forgiveness, acceptance, enlightenment, and empowerment and these elements, as have been alluded to, are similarly abundant in Pecado and Gracia. The artist and all men require forgiveness for our sinful desires and treatment of women, while we similarly require the strength to avoid the temptations that would force us into commitment of these acts.

In a similar fashion, we might infer that Romero himself is seeking forgiveness for his own actions – born of uncontrollable passion like Phaedra – and how they may have led to the persecution of an innocent woman. He, like all of us, should seek redemption (a theme that echoes throughout La Gracia’s background imagery, with the Cemetery of San Raphael as well as the churches of Fuensanta and Santa Marina all bound by the common them of healing),[xi] and it is possible to view these paintings as an act of his own atonement and desire for forgiveness. Here it becomes additionally relevant to consider that, as a person renowned for painting women in provocative poses (often nude), Romero was no stranger to scandal. Rumors that he was engaged in sexual relations with his models were apparently widespread in Córdoba, with Maria Teresa Lopez, the model of Romero’s most celebrated work, La Chiquita Piconera (examined in a separate post), reporting in interviews that she had been a victim of vicious rumors that claimed she had been sexually involved with the artist. These rumors subsequently haunted her throughout much of her life and had a profoundly negative impact on her. Meanwhile, rather than being derided as a pedophile (Lopez was only 16 when she posed for him) or shamed for his philandering and disregard for his marital vows, Romero is instead generally beloved in Spain. To spell this out more clearly: the male artist is adored for the same painting in which the female model is shamed. In this sense, one may see the sin in Pecado as posing for the artist, with the result being the crucifixion we observe in Gracia. In this way, Romero is providing a form of salvation for he is allowing his models to live on in eternity and obtain absolution.

Regardless of our interpretation, it is apparent that one’s view changes when examining El Pecado and La Gracia in tandem. Here again, we may derive one final insight from Euripides and the ultimate lesson instilled in Hippolytus: that our judgments, made with incomplete information and without proper contextualization, are so often wrong. These two works require that they be viewed in unison in order for the proper dialogue to occur and so that we may fully grasp the conflict being presented between spiritual and earthly desires. Only in this scenario can we then appreciate the larger brilliance of Romero’s work: his ability to portray a duality that resonates with the sons and daughters of Andalusia through the meaningful representation of their shared experiences in navigating life within a culture where earthly passion and Catholicism are contentiously embedded, respectively, in the local pathos and ethos. Much like a Saeta is able to merge religious lyrics with tango singing and instrumentals, Romero displays an acute ability to capture these inherent tensions and communicate them in a style that resonates with a large segment of local society while also maintaining the integrity and beauty of each.

This, in my opinion, encapsulates the greatness of Romero de Torres and serves as the reason for why he was labelled the “first Spanish painter” by Ramón del Valle-Inclán. To further illustrate this, it is perhaps most illuminating to begin, somewhat paradoxically, with his death.

When Romero died in 1930 at the age of 55, it is reported that Córdoba went into a pronounced state of mourning. The municipal government immediately agreed to cover all costs of the burial, ensuring that no expense would be spared in putting together a proper sendoff for its prized son that would permit the populace to properly mourn and honor the artist’s passing.

The service took place in the city’s most famous landmark – the Mosque-Cathedral – and was followed by a lengthy procession through Córdoba’s old town, with a contingent of his models following the coffin as it made its way toward his final resting place in the San Rafael cemetery on the city’s outskirts.[xii] Shops, theaters, cafes and taverns were shuttered as the city came to a standstill so that everyone would be afforded the honor of a final glimpse at this man that they adored. Apartment windows along the procession path (as well as the city’s taxis) were adorned with black ribbons. Members of the local labor union donned their professional uniforms – a custom afforded only when honoring the death of one of their brethren. Poets penned elegies. Politicians put aside their intense vitriol and came out in a collective show of support. The city became united in the singular purpose of honoring and mourning Romero.

Although he had been battling liver disease for a prolonged period, Romero’s death was seen as tragically premature. His fellow Cordovans were unprepared, resulting in an emotional display of collective grief. It is important to pause for a moment and really consider the outpouring described. Perhaps it is more common in a place like Andalusia, but it seems almost inconceivable to imagine such a scene for someone with my cultural background. Only in the rarest and most tragic of instances could I envision such mourning (such as the assassination of Kennedy or King) and never would I imagine this directed towards an artist who died of natural causes. Yet, this is precisely what happened in Córdoba with Romero. The question is why. The answer, I contend, is that the people of Córdoba – regardless of class distinction or political affiliation – had lost the translator of their hearts and interpreter of their souls.

It is on these terms that I believe we should engage Romero’s critics who view his work as intellectually limited. This collective mourning for Romero reminds us of one of the foremost and fundamental values of art: its ability to articulate our collective meanings and communicate concepts that can be felt so strongly and understood so clearly by many of us, but which are difficult to transmit through more commonly accessible forms of communication such as speech, sound and body language. Art, in my experience, is so powerful because it can immediately overwhelm you with sentiments that were completely absent only a moment earlier, but which at once become clearly understood. The profoundness of this experience, is in turn, compounded by the sense of belonging that it engenders with our fellow human because one understands, immediately and intimately in that moment, that these feelings are fully shared by someone else.

In these instances, our lives are provided with a sense of validation and acknowledgement and reaffirm that we exist. We are provided with a sense of comfort – even if only fleeting – in seeing that there is a place for us in the universe. It is the sensation of finding the perfect word to describe your inner machinations and, at times, the articulation of feelings you had carried with you but couldn’t convey until that moment. Art, in these moments, represents the confluence of the individual and collective elements of our existence and the ability to unite these is one of the marks of a great artist.

Art can affect us in deeply personal ways, but I am suggesting that it may be at its most profound when it is able to delineate collective experiences and emotions and communicate these effectively. We are, at our core, individuals who create and define our existence, but we are inherently social and, I would claim, only able to extract the most meaning from our lives through belonging. Art, similarly, has a crucial role for individual expression and creativity, but it can only be a cultural act to the extent that it is shared. Romero, in his ability to transpose his city and its culture onto canvas did just that. He communicated the meanings and values of his fellow Cordovans in a way that surpassed what was possible with words alone.

We are blessed to have cultivated so many wonderful men and women who bind us together through the feelings and messages that their art invokes. Many of us tend to be partial to particular artists or styles that we more closely identify with – those whose works speak to us more directly. You, like many, may find yourself particularly disposed towards Van Gogh, while I might be more inclined towards O’Keeffe. Some spend their time in the impressionist wing of the museum, while others while away among the abstract expressionists. Imagine, though, that there was instead a single artist that spoke to all of us? This, I contend, is what Romero de Torres did with the people of Córdoba and this is why he was mourned so deeply by his fellow citizens.

There is a decent chance that you have (I hope) had the experience of staring at a piece of art and finding yourself truly moved. If you have, I would ask that you recall how wonderful such moments are. If you’ve had this occur while at a museum, you might also have been blessed to subsequently look over at fellow patron gazing at the same work and noticed them sharing your experience. If so, you understand how this magnifies the feelings that took hold of you in that moment. Imagine now that you had shared this experience with everyone around you in the town or city where you live. Imagine the admiration you would have for the provider of such a gift: the person who peered into your soul and drew it for you so that you could see what it looked like; the person who plucked on the strings of your heart like those of a Spanish guitar, bringing forth a Solea that sang out the words it struggled to say. This is what I am suggesting Julio Romero de Torres was to his fellow Cordovans. Even if his message couldn’t be received as clearly outside of his city’s borders – becoming further diluted the further it went, like words along a chain in a child’s game of “telephone” – I can come to no other conclusion than that he must have been a great artist, for he captured the true essence of his fellow citizens as they themselves experienced it.

Make no mistake, Romero de Torres is the Córdoba of his age and his art is, in a large way, a means of understanding the culture that inspired him.

[i] We can observe a range of Córdoba’s notable landmarks here: on the left we have the San Rafael Cemetery and church of the Virgin of Fuensanta. Further in the distance we can see the Guadalquivir river including the Roman Bridge, the Calahorra Tower and the neighborhood of Campo de la Verdad on the river’s opposing bank. On the right, we have the façade of the church of Santa Marina followed by San Lorenzo and the Mosque-cathedral.

[ii] This work is likely influenced by the Titan painting from 1515 of the same name – particularly as Titan is often cited as having a notable influence on Romero.

[iii] I am not, however, prepared to argue against this overall critique of Romero de Torres as I haven’t devoted enough research into his entire body of work. His notable emphasis on young women (often nude) could understandably incline the more modern viewer to see his work as promoting objectification of women and I think this critique deserves to be taken seriously (though I also remain skeptical of it). In this regard, his work Naranjas y limones (1927) seems to be an easy target and is particularly cringe-worthy at first glance.

[iv] The name Hippolyta, interestingly, derives from the ancient Greek roots for “horse” and “let loose”. Such a name is, therefore, fitting for a discussion on the pitfalls of unbridled passion.

[v] Similarly, the name Hippolytus has a fitting translation in Greece since it derives from the roots for “horse” and “loosen, destroy”. So, while it can be a kind of badass interpretation such as “unleasher of horses” it may also be read as “destroyed by horses”. Pretty genius then that he is eventually destroyed by horses.

[vi] Indeed, in both versions of the play, Phaedra struggles to overcome her passion, knowing that her lust for Hippolytus is a sin. However, she cannot overcome the physical urge. In this sense, it is possible that Romero is experiencing similar sentiment – and perhaps even trying to cajole his muse into succumbing to him. One could imagine the words spoken to Diana (Roman version of Artemis) by Phaedra’s Nurse as reflective of Romero’s own desire for his muse: “Tame grim Hippolytus’ unyielding spirit, make him listen favorably, soften his wild heart. Let him learn love, to receive and return the flames of passion. Change his thoughts; make that grim, spiteful, fierce man yield to the sovereignty of Venus”.

[vii] In this myth, Eris, the goddess of discord, again reacts in a manner typical of Greek gods (and 21st century teenagers) by seeking revenge in response to the slight of not being invited to the party thrown by Zeus in honor of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis (the parents of Achilles). Eris – totally justifying why she wasn’t invited – decides that the only befitting response to this snub is to ruin the wedding. So, she heads down to the Garden of the Hesperides and picks a golden apple out of Hera’s orchard. She then sneaks into the wedding ceremony, inscribes “to the fairest” on it, tosses it into the proceedings and watches the chaos ensue. This apple is simultaneously claimed by Hera, Athena and Aphrodite who – channeling their inner teenagers – argue over who rightfully deserves the trophy and superlative of “best looking” in the annual yearbook. Knowing the can of worms that he’ll open if he gets involved, Zeus passes the buck and decides that Paris, mortal prince of Priam should be the umpire in this affair. After judging all three, Paris awards the apple to Aphrodite under the promise that she will grant him Helen of Troy in return. Paris sails to Troy to redeem his prize voucher and yada, yada, yada: Trojan War, big wooden horse, Achilles killed, Odysseus takes the scenic route home.

[viii] It is worth considering as well the parallel with the Rokeby Venus. In the latter, the mirror is held by Venus’ son, Cupid. Here, it could be that the mirror is being held by her mother, again reflecting the future that awaits this physical beauty.

[ix] It seems, as well, that Romero may be providing a commentary on the manner in which a woman’s value is determined. Still persisting today, a woman in Romero’s age would have been exceedingly limited in economic and political participation, with her value based largely on her physical appearance. In Paris’ choice of Aphrodite, it is worth acknowledging that he chose sexuality and beauty over wisdom and glory.

[x] In the presence of the nuns, we are reminded as well of their own vows of celibacy and how this contrasts with the female protagonist who appears to have been vilified for apparent sexual impropriety. Returning to Hippolytus, however, it is important to note that Euripides portrays the male protagonist’s chastity as a sin – an affront to Aphrodite and anathema to our very nature which requires the act in order to sustain our species. This further complicates what appears, prima facie, as a clear juxtaposition between right and wrong and sacred and profane. Just as we should question the morality of our socially determined views regarding female sexuality, Romero introduces questions as to the morality of celibacy among nuns.

[xi] Raphael translates as “god heals” in Hebrew, while Saint Raphael is renowned for his power to heal. In the Church of Fuensanta, moreover, we are presented with the co-patron saint of Córdoba, who is said to heal whoever drinks from her well. Similarly, when Santa Marina was martyred, the “Aguas Santas” were said to have sprung forth from the points where her severed head hit the earth. These too are said to heal all who drink from them.

[xii] Sources:

Salcedo, M. 2003.“El Entierro del Pintor”, Diaro Córdoba

Miranda, Luis. 2014. “El día en que a Córdoba se le murió el alma”, ABC de Sevilla

https://rutacultural.com/julio-romero-de-torres-pintor-alma-cordoba/

Annex: summaries of Hippolytus by Euripides and Phaedra by Seneca

Picking up from the point in Hippolytus where Phaedra falls madly in love with Hippolytus, it should be noted that this occurs in the context of a period of enforced separation between the former and her husband, Theseus. Theseus, you see, is away serving a year of voluntary exile in atonement for the teensy, tiny transgression of murdering the rival heir to the Athenian throne, Pallas, and his 50 sons (who are also, respectively, his uncle and cousins). Phaedra begins to become overwhelmed by her love for Hippolytus, finding herself love sick and unable to eat. At odds over what to do, she eventually communicates her love to her nurse (who is adamant in her desire to find out what is ailing her queen), but seems resigned to kill herself rather than act on it (knowing that to act would only bring shame to her and her family). Her faithful nurse, practical in her old age, argues that it would instead be better to voice this love to Hippolytus, which she does on the Queen’s behalf. (This is a noteworthy distinction from the Seneca version, where Phaedra directly communicates this love to Hippolytus).

Hippolytus, as a man of profound honor, is predictably disgusted by the nurse’s proposal and vehemently rejects it. However, as he had previously sworn a vow of secrecy to the nurse, he is barred from informing his father of his wife’s infidelity. Phaedra and the nurse, however, are concerned that Hippolytus will dishonor this vow. So, out of horror from the shame that this, once exposed, would bring her, they agree that Phaedra’s only recourse is to kill herself. To retain her honor and ensure that her two children may keep their claim to the Athenian throne (and to also punish Hippolytus for his arrogance),[i] she pens a suicide note claiming that her act was carried out in response to the shame of being raped by Hippolytus. Phaedra hangs herself shortly before Theseus’ unannounced return, with the latter arriving just as servants remove her dead body from the noose.

The king of Athens is devastated, pleading for death and searching the heavens for an explanation to help make sense of such a senseless act. It is in this moment that he finds the suicide note and discovers the accusations leveled against his son. His despair immediately shifts to outrage and he publicly banishes Hippolytus from his lands (an act that was nearly akin to a death sentence in ancient life). Recalling as well that Poseidon owes him “three curses”, he calls on the god of the sea to bring death to Hippolytus. The latter strolls into the palace to greet the return of his father, unaware of what has befallen Phaedra.

Upon hearing the charges laid against him by his father, Hippolytus is at first shocked then similarly outraged at having his honor unfairly besmirched. He unleashes the finest monologue of the play in his defense – honoring the vow of secrecy that had been given to the nurse and protecting the truth about Phaedra – but Theseus is not swayed and informs Hippolytus that the banishment will be upheld and that he must depart immediately.

Hippolytus obeys, boarding his chariot and setting off with a group of servants. On his way out of Athens, he is beset by a colossal wave, summoned by Poseidon, which also brings forth a giant bull. Despite being a skilled rider, Hippolytus’ horses panic and eventually the chariot capsizes and he gets tangled in the reins and dragged behind the horses for some distance, hitting his head on a number of rocks along the way. A messenger arrives at the palace to inform Theseus of what has happened to his son. At first, Theseus sees it as divine justice, but is then visited by Artemis who reveals the truth of the situation. The false accusations made by his wife are seen as forgivable acts since they were not her own doing, but rather orchestrated by Aphrodite. Hippolytus’ body is returned to the palace, still alive but clearly on the cusp of death. He offers some damning remarks, but ultimately forgives both Artemis and his father.

In the Euripides version, we are presented with a lesson of the value of temperance, with catastrophe shown to arise when actors engage in rash judgements born of anger and passion that are made when possessing only partial information. Passion is clearly portrayed as dangerous and destructive when not reined in, producing tragic outcomes for all characters involved. However, it is worth noting that the author similarly presents the ascetic and moral rigidity of Hippolytus as culpable in the events that unfold. In this, we find support for a middle path, ruled by reason, but also for calls for compassion and understanding of others. The story goes to lengths to show how passions destroy all the characters involved, but it also forgives those who are tempted, since it casts them as victims of love’s will – something beyond human control and determined by the gods.

While the general plot of Phaedra is largely consistent with the Euripides version, Seneca introduces several important deviations from the original. In this version, the gods’ direct involvement is eliminated. Further, the backstory surrounding Theseus’ absence is altered, with him being trapped by Hades in the underworld following his botched attempt to help his BFF, Pirithous, abduct Hades’ wife, Persephone. Imprisoned already for four years in a place thought to be inescapable, Phaedra has made up her mind that her husband is as good as dead and never coming home. This helps underscore the longing for companionship felt by Phaedra and provides a motivation for her seeking to act upon her desires for Hippolytus. This then leads to the main departure, where Phaedra is ascribed greater agency in her actions and, therefore, viewed much more culpable in the tragedies that unfold.

In the Seneca version, we are also required to attach greater importance to the family background of Phaedra and Theseus and the complex relationship between Athens and Crete (of which Phaedra was a princess). This gives us a framework for understanding why Phaedra is made to fall in love with Hippolytus since, as I’ll explain, it is due to Aphrodite’s hatred for Helios (rather than jealously over Hippolytus choosing Artemis as in the Euripides version).

Phaedra is daughter to King Minos, son of Zeus and Europa, and Queen Pasiphaë, daughter of the Titan sun-god Helios. In this story, Venus (the Romanized version of Aphrodite) is again behaving exceedingly mature and enacting vengeance against all decedents of Helios. You see, as the god of the sun, Helios is able to see pretty much everything that happens under his domain and one day spies Venus, wife of Vulcan (the Romanized version of Hephaestus), having an affair with Mars (Ares). Helios tells Vulcan of his wife’s infidelity, causing the latter to tap into his renowned rage. Channeling this anger, Vulcan lays a trap that allows him to (literally) catch the two in the act by ensnaring them in a net. As a further act of revenge, he then drags them – naked and still in the net – to Mt Olympus so that they could be publicly shamed in front of all of the other Gods. Venus is not terribly pleased at being dragged naked in a net and shamefully displayed in front of all the cool kids at Mt. Olympus High School, so she decides that, rather than engaging in some self-reflection and marriage counseling, the only proper response is to blame Helios. Abiding by the ancient and godly wisdom of “snitches get stitches”, she decides to use her position of power to curse all human offspring of Helios (since she is unable to punish him directly).

Venus’ curse is directly relevant to the story for two reasons. First, because Phaedra is a granddaughter to Helios (making her a prime target for the goddess of love); and, second, because it forces all who receive it to be subject to a life of abnormal romantic relationships. Venus, as we’ll soon see, does not fuck around. To begin, she makes Phaedra’s mother, Pasiphaë, fall madly in love with a white bull that had been gifted to Minos by Neptune (Poseidon), but which Minos secretly decides to keep alive because it’s just too damn lovely. (So, Neptune helps Venus out here by recommending that she make Pasiphaë fall in love with the bull, so that the two can both get revenge at the same time).

Afflicted with Venus’ curse, Pasiphaë ends up really wanting to consummate the intense passion she feels for the bull. It turns out, however, that it’s not so easy to get a bull to have sex with you when you, yourself, are not of the same species. So, she enlists the famed Athenian inventor and master craftsman, Daedalus, who constructs a device that is, more or less, a Trojan Horse for bull fornication and perhaps history’s first gloryhole. The device works: Pasiphaë hides inside, the bull mounts the wooden cow, and the latter can’t tell the difference in the “blind vagina taste test”. The good news is that the bull’s large reproductive organ doesn’t kill Pasiphaë; the bad news is that she becomes pregnant and, some months later, gives birth to the dreaded Minotaur – who starts eating humans once his mother stops breastfeeding him.

Minos, King of Crete, subsequently faces a bit of a conundrum. His wife had cheated on him with a bull that he was supposed to kill and given birth to a monster that is currently killing his subjects. For reasons I don’t quite understand, his solution is to try to sweep it all under the rug: he stays with his wife and doesn’t kill the Minotaur, opting instead to have it imprisoned. For this, he again calls on Daedalus, having him construct the famed Labyrinth to serve as the beast’s dungeon.

While this seems to resolve the crisis, another eventually emerges in Athens. Minos’ son (and Phaedra’s brother), Androgeus, is a total stud and takes home all the glory from the quadrennial Panathenaic Games (precursor to the modern Olympics). Gracious losers that they are, some of his Athenian competitors handle this defeat well and decide to kill Androgeus (what else is one supposed to do in an era before performance enhancing drugs?). Minos, understandably a little sore that his son and heir was murdered by history’s first player-haters, wages war against Athens (then ruled by Theseus’ father Aegeus). The former wins and, as punishment, forces Athens to surrender 14 of its best young men and women every 7 years to be sacrificed to the Minotaur.

After a couple rounds of this, (then) Prince Theseus decides that the madness must stop and volunteers to be included among the 7 sacrificial young men so that he can kill the Minotaur and free Athens from the tyranny of Crete. Setting out on a ship with a black sail, he tells his father that the fate of this quest will be communicated by the color of his sail upon his return: black will imply that he is dead, while white will signal success.

Arriving in Crete, the young Athenian men and women are prepared for their forthcoming sacrifice to the Minotaur and have their weapons seized beforehand. However, Venus, still out to punish Helios, decides to make Phaedra’s sister, Ariadne, fall madly in love with Theseus. Ariadne then decides to forsake her family and country by conspiring to assist her new love in his quest to kill her half-brother, the Minotaur, by providing him with a sword and a ball of twine to be used to retrace his steps out of Daedalus’ Labyrinth.

The plan works: Theseus kills the Minotaur, escapes the Labyrinth, sneaks aboard his boat (together with Ariadne, Phaedra and the other sacrificial Athenians who had accompanied him) and sets sail for Athens. Along the way, they make a pit stop on the island of Naxos for rest and supplies. Love struck Ariadne falls asleep and when she wakes, she discovers that her dream man, Theseus, is a total gentleman and took off without her, leaving her to die on the island. As a final “fuck you”, we learn that Theseus left instead with Phaedra, who he eventually weds.

The ship that had initially set sail for Crete finally arrives safely in Athenian waters and Aegus is alerted to the return of his son’s vessel. In the midst of all the drama, however, Theseus had completely forgotten to swap out his black sail for the white one to signal to his father that his quest had been a success. Glancing into the harbor from his vantage point atop a cliff, Aegus observes the black sail and, distraught over the apparent demise of his son, commits suicide by casting himself into the sea (granting his name to what we today know as the Aegean Sea).

This family background is relevant because it contextualizes the manner in which Seneca portrays Phaedra’s lust for her stepson, Hippolytus. It is – like Pasiphaë lusting after a bull – unnatural and wicked. This is clearly implied in the Euripides version, but Seneca takes greater efforts to paint the female protagonist as the cause of the story’s tragic results. To this end, Phaedra is portrayed as more cunning and given a greater degree of agency so that she can more convincingly be cast in the “temptress” role often developed in different historical works of literature and mythology. To this end, the opening scene has her openly voicing her displeasure for Athens and the house of Theseus, thereby portraying herself as a spiteful person out for revenge.

In the Seneca version, Phaedra also directly communicates her love to Hippolytus (in contrast to the Euripides version, where it is the nurse who carries out this act). The latter again rejects these advances, leading to a different (and far more cunning) plot from Phaedra and the nurse than observed in the original. Hippolytus, disgusted by Phaedra’s advances, becomes enraged and drags her by the hair before the altar dedicated to Diana (Artemis), brandishing his sword as he gestures violently. Recognizing the fortuitous optics of the scene, the nurse calls on others nearby to come forward and bear witness to what she claims is Hippolytus trying to rape Phaedra and threatening her with death.

Theseus miraculously returns, having escaped from the Underworld, with Phaedra still alive (unlike in the Euripides version). As he approaches the wife he has not seen in four years, Theseus finds her sobbing while clasping the sword of Hippolytus (which he had clumsily left behind in his fit of rage). It is a brilliant performance by Phaedra and her husband buys it. Theseus erupts and swears to kill Hippolytus, again calling on Neptune to carry out his bidding. Hippolytus’ dead body is brought before him in the palace and he mourns his son’s passing despite retaining a feeling of validation for his role in the death. Phaedra enters, still carrying Hippolytus’ sword and breaks down in tears upon seeing her love’s dead body. In an act of anguish, she kills herself, confessing that the story of rape was fabricated and a premeditated plot. Theseus is now devastated over the loss of his son and disgusted with his wife. A funeral pyre is prepared to honor Hippolytus and the play concludes with: “As for the woman, dig a grave and cover her body with soil – may the earth weigh heavily upon her wicked soul.”

[i] Euripides’ play does not absolve Hippolytus of all blame. He is portrayed as too rigid and arrogant in his virtues. He treats others without compassion and does not display a desire to understand the context that gives rise to their actions and emotions. In this respect, in the beginning of the play, he is warned by an advisor that he is inviting trouble by scorning Aphrodite and choosing to honor only Artemis, yet he sticks obsequiously to his principles and ignores this counsel. That isn’t to say that he should’ve just slept with his stepmother, but had he not been so strict in his temperance, he would not have aroused the ire of Aphrodite, leading to the tragic events.